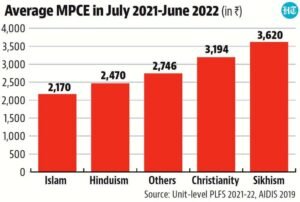

An examination of the socio-economic status of Muslims in India reveals that the country’s largest minority is often perceived as a homogenous community. However, this perception is far from reality. Deep social and economic disparities exist within Indian Muslims, shaping their daily lives, opportunities, and prospects.

A majority of Indian Muslims — over 80 percent — belong to backward or marginalized groups. The term Pasmanda, of Persian origin, literally means “those who have been left behind.” These groups largely consist of artisans, peasants, laborers, and service providers, locally referred to as Ajlaf and Arzal. In contrast, the Ashraf class identifies itself as socially superior, often claiming foreign descent or noble lineage.

A majority of Indian Muslims — over 80 percent — belong to backward or marginalized groups. The term Pasmanda, of Persian origin, literally means “those who have been left behind.” These groups largely consist of artisans, peasants, laborers, and service providers, locally referred to as Ajlaf and Arzal. In contrast, the Ashraf class identifies itself as socially superior, often claiming foreign descent or noble lineage.

The backwardness of the Pasmanda Muslims is not merely religious but deeply rooted in historical caste hierarchies that have restricted their access to education, livelihoods, and mobility. State policies have also tended to overlook these internal disparities, thereby reinforcing inequality. This article seeks to analyze these social and economic issues, particularly in the context of globalization and liberalization, to understand how historical marginalization continues to shape the present condition of Indian Muslims.

Caste Structure and Social Hierarchies among Muslims

To comprehend the backwardness of Indian Muslims, one must first understand their internal social stratification. Although Islam preaches equality and justice, caste-like structures exist among South Asian Muslims, reflecting the influence of the broader Hindu social order.

At the top of this hierarchy are the Ashraf — Sayyids, Sheikhs, Pathans, and Mughals — historically associated with religious scholarship, land ownership, and political power. Below them are the Ajlaf, consisting mainly of converts from artisan and agrarian backgrounds such as weavers (Ansari), barbers (Salmani), blacksmiths (Saifi), tailors (Idrisi), and butchers (Qureshi). At the bottom lie the Arzal, communities of Dalit origin who adopted Islam but continue to engage in stigmatized occupations.

The hereditary nature of these occupations has perpetuated limited social mobility. Consequently, despite Islam’s egalitarian ideals, caste-based discrimination persists within South Asian Muslim society. This demonstrates how deeply entrenched the caste mindset has become, transcending religious boundaries.

Colonial Rule and Economic Decline

The economic decline of Indian Muslims can also be traced back to British colonial policies. The colonial economy turned India into a supplier of raw materials and a consumer of British industrial goods. As a result, traditional handicrafts and cottage industries — heavily dependent on Muslim artisans — suffered immense losses.

Centers such as Varanasi, Mau, Moradabad, and Lucknow, once renowned for fine textiles and craftsmanship, witnessed a sharp decline. After the 1857 uprising, Muslims were collectively stigmatized as rebels, further damaging their economic prospects.

The replacement of Persian with English as the administrative language pushed the Muslim elite out of bureaucratic power. But the greatest setback was suffered by artisans who neither owned land nor benefited from emerging industrial capitalism. After the 1947 partition, many educated and influential Muslims migrated to Pakistan, leaving behind a weakened leadership among Indian Muslims.

Economic Liberalization and the Crisis of Traditional Occupations

Post-1990 economic liberalization and globalization further eroded the economic foundations of traditional Muslim occupations. Industries such as handloom weaving, leatherwork, and handicrafts — once the economic backbone of Muslim artisans — have been severely disrupted by mechanization and mass production.

The spread of powerlooms nearly wiped out the handloom sector. In states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, millions of weavers, cobblers, butchers, and blacksmiths have been pushed into informal, low-wage labor without job security or social protection.

According to the Periodic Labour Force Survey (2019–20), nearly half of urban Muslims are self-employed, mostly in low-income sectors like manufacturing and construction. This indicates that economic reforms have disproportionately marginalized traditional Muslim communities.

Landlessness and Indebtedness

Landlessness remains a major cause of economic vulnerability among Muslims. In Uttar Pradesh, nearly half of Muslim households own no land at all, and those who do possess very small plots.

Limited access to formal banking and credit compels many Muslims to borrow from moneylenders at exorbitant interest rates. These debts are often incurred for social expenditures such as marriages or medical emergencies, deepening their financial insecurity.

Urban Muslims face higher poverty rates than their rural counterparts — a sign that the decline of artisanal economies has hit urban Muslim communities especially hard.

Educational Deprivation and the Cycle of Poverty

Educational deprivation is the most significant barrier to the socio-economic progress of Muslims. High illiteracy rates, low school retention, and limited access to quality education have excluded Muslim youth from government employment and modern professions.

The Sachar Committee Report (2006) and Kundu-Mishra Commission highlighted that Muslims, particularly from backward castes, are among the most disadvantaged sections of India’s labor force.

The Social Justice Committee Report (2001) in Uttar Pradesh found that although Muslim OBCs constitute a large portion of the state’s OBC population, their representation in higher government services (Class A and B) remains negligible. The benefits of affirmative action have largely been cornered by dominant Hindu OBC groups, leaving Muslim OBCs marginalized once again.

Political Discourse and Policy Challenges

Economic deprivation has triggered a growing awareness of caste identities and demands for equitable representation within the Muslim community. Since the 2000s, the Pasmanda Movement has foregrounded caste-based inequalities and challenged the dominance of the Ashraf elite in Muslim leadership.

The current government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi has sought to politically engage backward Muslims, with reports suggesting that the upcoming 2026 Census may formally recognize Muslim backward castes within the Other Backward Classes (OBC) framework.

However, unless this move is accompanied by institutional empowerment, educational access, and economic opportunities, it risks remaining a mere act of tokenism rather than genuine reform.

Policy Recommendations

Meaningful progress for backward Muslims requires policies that address caste-based deprivation rather than relying solely on religion-based welfare schemes.

1. Data Collection: Conduct caste-disaggregated surveys among Muslims to design targeted interventions.

2. Economic Empowerment: Provide low-interest loans, microfinance, and market access for artisans and small entrepreneurs.

3. Education: Expand scholarships, residential schools, and vocational training centers.

4. Skill Development: Integrate traditional crafts into modern value chains to prevent displacement.

5. Political Representation: Ensure the inclusion of genuine Pasmanda representatives in policy implementation.

The socio-economic status of Pasmanda Muslims reveals the deep-rooted intersections of caste and class within South Asian Islam. Despite being the majority among Muslims, they remain economically and politically marginalized. Their craftsmanship — once a source of dignity and self-reliance — now struggles against capitalist modernization and systemic exclusion.

In many parts of North India, poverty, illiteracy, landlessness, and lack of political participation continue to prevail. Unless policy frameworks recognize and address these internal inequalities, the promise of equality and justice will remain unfulfilled.

This struggle is not a plea for charity but a demand for structural reform — an acknowledgment that caste hierarchies persist even within a religion that preaches equality. Only through such honest recognition and concrete reforms can India move toward becoming a truly inclusive democracy.

Muhammad Yunus

Muhammad Yunus

Chief Executive Officer

All India Pasmanda Muslim Mahaz